Performance Plates: The Athlete’s Guide to Daily Fueling

Intro to Performance Plates

Our day-to-day nutrition practices establish our fueling foundation, which supports both general health and athletic performance. To learn about the basic pillars of nutrition, check out the previous blog, Nutrition 101. As a quick recap, we need to establish macronutrient and micronutrient adequacy in order to live and train well. Macronutrients - protein, carbohydrates, and fat - make up the majority of what we eat and are essential for energy and body function. Micronutrients, or vitamins and minerals, are smaller, yet highly important components of our intake that do not directly supply the body with energy, but support various internal body processes. Since each macronutrient and micronutrient plays a unique role in the body, it’s crucial to maintain a diet that provides both enough nutrients and a variety of nutrients. With that being said, if we had to track our precise intake of each macronutrient and micronutrient, we’d probably eventually start to feel overwhelmed by even small nutrition decisions. While tracking dietary intake can be a helpful short-term tool, many of the athletes that I work with benefit from using a simpler tool called “performance plates.”

Performance plates, also known as “athlete’s plates,” were developed by a collaboration between the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) Sport Dietitians and the University of Colorado Sport Nutrition Graduate Program. They are a tool that can be used by athletes of all levels to implement nutrition periodization, which involves varying dietary intake according to training demands. In simpler terms, performance plates can help us understand how to build meals that support our body’s needs on different types of training days.

Building a Balanced Meal

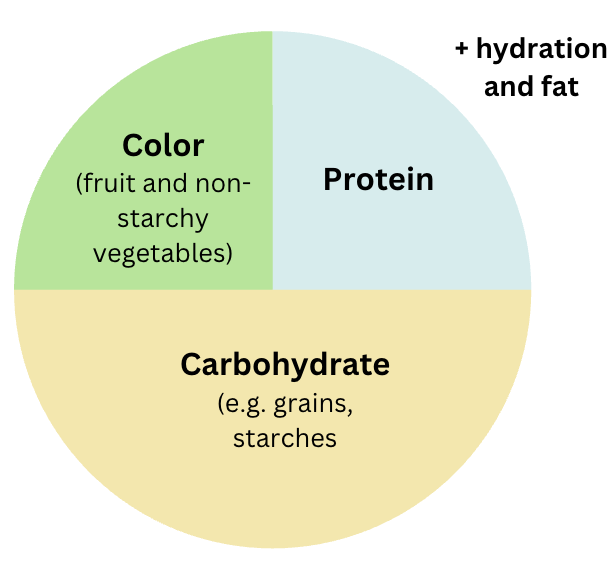

Most athletes benefit from eating at least every ~3-4 hours across the day. This typically works out to be 3 meals and anywhere from 1-3+ snacks depending on training load, schedule, goals, etc. Ideally, each meal should contain a source of protein, carbohydrate, fat, and “color” (fruit and/or non-starchy vegetables). Including these components with each meal helps ensure that you meet your macronutrient/micronutrient needs and get sustained energy from the meal that you eat.

Let’s review some common food examples for each macronutrient. Remember, many foods contain more than one macronutrient and you will therefore see some of the same foods listed for multiple macronutrients below.

Protein - Examples include meat, seafood, soy products like tofu, tempeh, and edamame, dairy products like milk, yogurt, cheese, and cottage cheese, eggs, beans, lentils, and nuts.

Carbohydrate - Examples include bread, pasta, cereals and grains like rice, quinoa, and oats, dairy products, beans, fruits, and vegetables.

Fat - Examples include meat and dairy products, seafood, eggs, avocado, coconut/coconut oil, olive oil and other plant oils, butter, chia seeds, flax seeds, and nuts/nut butters.

“Color” (fruit and/or non-starchy vegetables) - Fruit examples include apples, bananas, berries, oranges, grapes, and melon. Non-starchy vegetables contain minimal starch and are therefore lower in carbohydrates and calories compared to starchy vegetables like potatoes, winter squash, peas, and corn. Examples of non-starchy vegetables include lettuce and other leafy greens, bell peppers, cucumbers, carrots, broccoli, cauliflower, mushrooms, and zucchini.

Fruit and non-starchy vegetables are technically carbohydrates, so you might wonder why I’m classifying them as “color” instead of carbohydrates. I make this distinction because 1) these foods are typically significantly lower in carbohydrates per serving compared to grains and starchy vegetables, making it difficult to rely on them alone to meet an athlete's elevated carbohydrate and energy needs; 2) the primary nutritional value of colorful produce is the vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and fiber that they provide. By treating fruit/non-starchy vegetables as a separate category, we ensure that these nutrient-dense foods remain a consistent part of the plate while still leaving room for the energy-dense carbohydrates that athletes need to fuel performance.

Classifying Training Days

In order to put performance plates into practice, we need to understand how to classify different types of training days. The descriptions below might not be a perfect match for your exact training style/load, but can offer a general starting point:

Rest day or easy training day = Little to no activity (full rest day) or up to ~1 hour of easy effort training (e.g. walking, mobility training, low effort biking)

Moderate training day = About 1-2 hours of easy effort training or up to 60 minutes of high intensity interval training; appropriate for a team sport athlete’s practice day. This is typically the baseline plate from which an athlete adjusts their plate down (for easier days) or up (for higher intensity and/or longer duration activity).

Hard training day = More than 2 hours of easy effort training or more than 60 minutes of high intensity interval training; game day, race day, or double training days

The training classification guidelines above are a blend of guidance from the USOPC and fellow dietitian Kylee Van Horn’s book, Practical Fueling for Endurance Athletes.

Adjusting Meal Composition for Different Training Days

As you’ll soon see with the performance plate visuals, the general idea is that carbohydrates should make up a greater proportion of your plate on harder training days. This is because our body relies on energy from carbohydrates to power muscle contractions during high intensity activity. Additionally, longer duration training depletes glycogen, the storage form of glucose in the liver and muscles. In order to replete glycogen stores, we need to consume sufficient carbohydrates. In simpler terms, our main physiological need on high training days is readily available energy, which is primarily provided by dietary carbohydrate intake. So, it makes sense that the higher intensity and/or longer duration activity characteristic of “moderate” and “hard” training days requires more carbohydrate intake at meals. Eating more carbohydrates on higher effort days also has the downstream effect of increasing total caloric intake, which is necessary in order to ensure that our energy intake matches the higher energy demands that come from harder training. For the most part, protein and fat needs remain fairly consistent across training days because they are not the primary sources of fuel used during activity. While our body does use fat for fuel during training, it primarily relies on our internal fat stores for this purpose and we do not need to meaningfully increase our dietary fat intake to enhance performance. In fact, eating a high-fat meal prior to training can contribute to gastrointestinal upset because fat slows gastric emptying, meaning that food stays in your stomach for longer. The combination of delayed digestion plus reduced blood flow to the gut during exercise can cause discomfort.

Rest Day or Easy Training Plate

25% protein, 25% carbohydrate, 50% color

Use on a full rest day or a day with easy and short-duration training, e.g. up to ~1 hour of easy effort training (e.g. walking, mobility training, low effort biking)

Moderate Training Plate

25% protein, 37.5% carbohydrate, 37.5% color

Use on a day with approximately 1-2 hours of easy training or up to 60 minutes of high intensity interval training. This is the baseline plate for most athletes and active people.

Hard Training Plate

25% protein, 50% carbohydrate, 25% color

Use on a day with more than 2 hours of easy effort training or more than 60 minutes of high intensity interval training

** The models above can provide a general starting point, but are not a substitute for individualized nutrition guidance. Be attentive and responsive to your hunger cues. It’s okay to eat more, even if it doesn’t match the performance plate model for your training day.

Some nutrition practitioners share performance plate models that increase fat and protein intake as well as carbohydrate intake on harder training days. This may be an appropriate strategy in certain situations, such as when athletes have very high energy demands and need to increase dietary intake substantially to meet calorie needs. However, for most athletes, focusing on increasing carbohydrate intake, keeping protein consistent, and adjusting fat intake slightly based on hunger cues is an adequate starting point. I recommend working with a dietitian or sports nutrition professional to understand how to implement performance plates based on your training and health goals.

Practical Tips for Using Performance Plates

Once you identify which performance plate is most appropriate for your training day, follow that model for all meals that you consume that day. In other words, if you have a 3-hour long run planned, you should use the “hard” training day plate for breakfast, lunch, and dinner that day.

If you have less than ~2 hours before you begin training, be mindful of the types of carbohydrates that you choose for your pre-training performance plate or snack. High fiber carbohydrates (e.g. whole grains, beans, etc.) take longer to digest and are therefore more likely to contribute to gastrointestinal distress when eaten too close to training time. The closer you are to the start time of your activity, the more important it is to opt for lower fiber, easier to digest carbohydrates. Some examples include low fiber cereal, fruit gummies, graham crackers, fig bars, sports nutrition gummies/chews/gels, etc. For example, if you eat breakfast ~2 hours before a long run, you might choose something like a plain bagel spread with jam, a low-fat yogurt, and a glass of juice. This meal provides ample easy to digest carbohydrates (bagel, juice) with a small to moderate amount of protein (yogurt) for satiety. Stay tuned for a later blog post on nutrient timing and more detailed information on how to structure pre- and post-training meals/snacks.

The performance plate model applies to main meals. Aim for snacks that contain at least two different macronutrients to support satiety and energy levels. Examples include:

Apple (carbohydrate) and peanut butter (fat/protein)

Crackers (carbohydrate) and cheese (fat/protein)

Cottage cheese (carbohydrate/fat/protein) + pineapple (carbohydrate)

Sandwich bread (carbohydrate) with peanut butter (fat/protein) and jelly (carbohydrate)

Though performance plates have been validated through scientific research and are widely used in sports nutrition settings, they should be used as a guide, not a rule. Don’t worry about perfecting the proportions of your plate. You can use these models as a starting point, then adjust your intake based on your personal hunger/fullness cues, as well as performance and health goals. For example, if you do a long run on Saturday, then take a rest day on Sunday and notice that you feel extra hungry on Sunday, you may want to consider following the “moderate” training plate instead of the “easy” training day plate. Or, follow the “easy” training plate, but add more energy-dense snacks throughout the day to make sure that you appropriately respond to hunger cues and meet your nutrition needs, knowing that this will support your recovery the day after a long run.

If you have questions about how much to eat, when/what to eat, and how to put the performance plate method into practice, reach out to me or book an appointment for individual consultation.