Nutrition 101

The Nutrition Basics Framework

There’s a lot of information in mainstream media about different diet protocols, ideal meal timing, supplements, and other nutrition trends. I find that mainstream nutrition conversations tend to be overly focused on minute details, when most people would actually benefit from zooming out and looking at their overall dietary pattern instead.

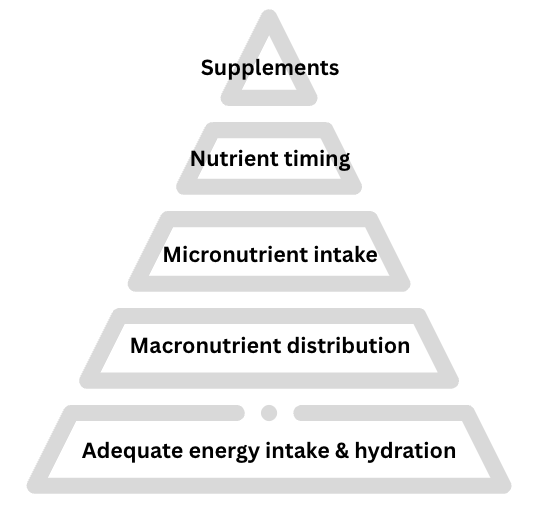

When I work with clients one-on-one, we almost always start out by reviewing what I call “The Nutrition Basics Framework,” pictured below. I use the components of this framework to highlight the different areas of nutrition that I’m trying to evaluate when I first meet with someone to learn about their health history, past/current dietary practices, relationship with food, physical activity/training, and more. I also like to use this framework to help my clients understand how they can do a quick diet audit or self check-in. This can be an especially handy grounding framework for clients who might be feeling overwhelmed by the nutrition information that they’re seeing online, in the news, etc.

How to Use the Framework

Here’s a brief description of each component of the framework, with some occasional notes for active people and athletes, one of the main populations that I work with:

Energy and Hydration Adequacy

From my perspective as a sports dietitian, adequate energy intake and hydration are the most important pillars of proper nutrition. If your energy intake and/or hydration are insufficient, you lack the necessary foundations for further higher level nutrition strategies. For example, if you’re not eating enough to meet your body’s energy demands, you’re likely not getting the maximum benefit from the supplements that you might be taking.

Adequate energy intake simply means eating enough calories (energy) to support internal body processes/physiological function and any other energy demands that are placed on the body, including the energy required for training/physical activity, digesting food, and activities of daily living. Energy needs depend on a variety of factors, including age, body composition/size, biological sex, training volume, genetics, and other lifestyle factors. For this reason, it’s difficult to provide specific calorie recommendations outside of the context of personalized one-on-one guidance between a client and a nutrition professional. Even in that context, there are cases when it may not be helpful to discuss food intake in the context of calories. If you want to make sure that you’re eating enough without thinking of food in terms or calories, first try to focus on eating consistently across the day, roughly every ~3-4 hours as a starting point. This timing should help guide you toward adequate intake without getting into the weeds of tracking calories.

Adequate hydration is vital to our cells and nearly all aspects of basic body functions. Like energy needs, fluid needs are highly variable across individuals. Age, physical activity level, body size, and environmental conditions are a few factors that impact our hydration status. There are different methods for estimating baseline fluid needs. One of the simplest methods is to take your weight (in pounds) and divide by two, which gives you a rough estimate of the number of ounces of fluid you should try to consume per day.

Weight (pounds) / 2 = approximate number of ounces of fluid you should aim to drink per day

For example, if you weigh 150 pounds, you’d aim to drink approximately 75 ounces of fluid per day. This equation provides a general starting point, which you can adjust as needed. If you don’t want to weigh yourself, you can monitor your thirst level and urine volume/color to get a general sense of your hydration status and adjust your fluid intake as needed. Try keeping a water bottle near you whenever possible and look for your urine to resemble a light lemonade or pale straw color to indicate adequate hydration.

Macronutrient Distribution

Macronutrients are major dietary components that we need in large quantities to provide energy and build/maintain tissues. The three macronutrients are carbohydrates, protein, and fat. Each macronutrient provides a certain number of calories per gram and plays a unique role in our body. Many foods contain a mix of multiple macronutrients. For example, most dairy products contain protein, carbohydrates, and fat. Basic food examples of each macronutrient are listed in the sections below.

Carbohydrates are often called the body’s “preferred” source of energy because they are easily broken down into glucose, which is the primary fuel for our cells. Some specific types of cells, like red blood cells, exclusively use glucose as their source of energy. Carbohydrates also provide fiber to support regular digestion and a healthy gut microbiome. Examples of foods that contain carbohydrates include bread, pasta, cereals and grains, dairy products, beans, fruits, and vegetables.

Most people know that protein provides the “building blocks” for our body’s tissues, but protein has many other roles in the body besides muscle growth. Enzymes needed for biochemical reactions and many hormones are derived from proteins. Protein also plays a role in immune function and can help transport molecules throughout the body. Examples of protein-containing foods include meat, seafood, soy products like tofu and edamame, dairy products like milk and yogurt, eggs, beans, and lentils.

Fat provides the most energy per gram of each of the three macronutrients and acts as a large energy reserve for the body. Fat also cushions and protects organs from injuries, insulates the body to aid thermoregulation, provides the building blocks for certain types of hormone production, and assists with the absorption of fat soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E, K). Fat is found in many foods, including meat and dairy products, seafood, eggs, avocado, olive oil and other plant oils, butter, chia seeds, flax seeds, and nuts.

While some specific diets/trends might encourage limiting a certain macronutrient, a healthful and sustainable dietary pattern for most people should include sufficient amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and fat. The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) are a set of scientifically developed reference ranges to help provide guidance on different nutrient intakes. These reference ranges are established based on a comprehensive review of current research and are updated as new evidence emerges. The DRIs specify an Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) for each macronutrient, which is a set of flexible guidelines for how much of each macronutrient most people should eat per day in order to meet baseline nutrient needs and support general health. The suggested AMDRs for each macronutrient are: Carbohydrate 45-65%, Protein 10-35%, and Fat 20-35%. The AMDRs offer a general starting point that can be adjusted to accommodate dietary preferences or specific health circumstances.

Micronutrients

“Micronutrients” is an umbrella term for vitamins and minerals. Our bodies need micronutrients in much smaller quantities than macronutrients (think, micro versus macro). Unlike macronutrients, micronutrients do not directly provide the body with energy, although some types of micronutrients participate in chemical reactions that help release energy from macronutrients. Micronutrients are critical for a wide variety of physiological processes, such as nerve function, fluid balance, oxygen transport, antioxidant protection for cells, immune function, and hormone pathways, to name a few.

Vitamins are organic compounds, meaning they contain carbon. Vitamins can be either fat soluble or water soluble. Fat soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K are absorbed with dietary fat and can be stored in the liver and fatty tissues in the body. Water soluble vitamins include vitamin C and vitamin B complex, which are absorbed in water in the body and are not stored long-term in the way that fat soluble vitamins are. Excess water soluble vitamins that are not used by the body are ultimately excreted through the urine.

Minerals are inorganic compounds, meaning they do not contain carbon. Some well known examples of minerals include calcium, magnesium, sodium, chloride, potassium, iron, and zinc. Some minerals, such as sodium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and chloride, function as electrolytes, which help manage fluid balance.

Most people are able to meet their micronutrient needs with an adequate and well balanced diet that includes a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables, whole grains, protein-containing foods, and fats. Since different foods/food groups each provide specific micronutrients, increasing dietary diversity is one way to help meet micronutrient needs. There are circumstances where people develop micronutrient deficiencies for one reason or another despite having a balanced diet. A common micronutrient deficiency is vitamin D. Vitamin D is produced in the body in response to sunlight exposure and is not found in many foods. People living in areas with limited sun might benefit from supplementing vitamin D to maintain optimal levels, especially during winter months. It’s typically best to get lab work done to determine if supplementation is warranted in the first place, as well as to determine appropriate dosing and then monitor your response to supplementation and/or dietary changes.

Nutrient Timing

Nutrient timing is a general concept that applies to big picture daily nutrition, but can also be applied more specifically too, like when an athlete wants to time their nutrient intake to support performance. The most basic aspect of nutrient timing involves nourishing yourself consistently across the day to support stable energy, reliable hunger/fullness cues, and stable eating patterns. For many people, eating three meals a day, then adding snacks to fill in any gaps is an appropriate starting point. This will likely involve some planning and possibly food preparation, depending on your schedule and other logistical barriers.

In addition to ensuring consistent food intake across the day, athletes can benefit from strategic nutrient timing. There are three main facets of nutrient timing for athletes to consider; before, during, and after activity.

Before: Consuming a carbohydrate-rich snack or meal and some fluid before activity provides the body with energy for the work ahead.

During: Consuming carbohydrates and fluid during endurance activities lasting longer than ~60 minutes helps maintain blood glucose levels, spare glycogen, and sustain performance.

After: Consuming carbohydrate, protein, and fluid after a workout helps replenish what was used during activity (e.g. glycogen, fluid lost in sweat), repair muscle tissue, and support short and long-term recovery from the activity.

Sports nutrition and hydration recommendations vary substantially depending on the type of activity, duration, environmental conditions, individual tolerance, and more.

Supplements

Dietary supplements are items taken by mouth that are meant to complement your daily food intake. Supplements may come in the form of pills, capsules, powders, gummies, or liquids and usually include vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbs/botanicals, or some combination of those things. Dietary supplements are not the same as conventional food/food products and are not as tightly regulated as food products. As a dietitian, I almost always recommend a “food first” approach, encouraging clients to meet most (if not all) nutrient needs with food/beverages first, then incorporate supplements if appropriate or necessary. For example, many individuals following a vegan diet can benefit from a vitamin B12 supplement unless they are consuming an adequate amount of B12 from fortified plant-based foods. Or, if someone has a diagnosed micronutrient deficiency (e.g. vitamin D, iron, etc.), this is a case where targeted supplementation, in conjunction with dietary counseling, can be very appropriate. There are of course other reasons that people seek out supplements beyond micronutrient concerns. For example, some athletes choose to use protein powder to help meet their daily protein intake goal in a convenient way.

I find that most people overdo it rather than underdo it with supplements. Again, supplements are meant to be complementary to food intake, and with some very few exceptions, one should not be relying on a supplement to fully meet their nutrient needs.

Putting It All Together

The nutrition basics framework is meant to highlight the importance of taking a “bottom up” approach to nutrition. Each level of the framework relates to the other levels, and levels that are lower in the framework are considered more foundational compared to levels higher up in the framework. For example, if you’re relying on a slew of supplements to meet your vitamin and mineral requirements, it might be time to revisit the lower levels of the framework. Working on energy adequacy, macronutrient distribution, and micronutrient intake/dietary diversity are all lower tier strategies that will help you better meet micronutrient needs in the long-term without relying on a supplement for a quick fix or bandaid. Similarly, research shows that meeting overall daily protein needs (macronutrients level of the framework) is more important than timing your protein intake immediately after your strength training session (nutrient timing level of the framework).

It’s tempting to jump straight to the top of the pyramid, but working on the lower levels first will likely serve you best in the long run. There’s a bidirectional relationship between each level of the pyramid and working on one component of your nutrition often leads to improvements in other areas of your nutrition too.

You can use this framework as a guide to more confidently evaluate nutrition information, navigate dietary decisions, and build a solid nutrition foundation to support your health and well-being. If you’re looking for help with this, schedule an initial assessment as a first step in getting individualized support.